It is very early in the morning, and there is a long line of people standing in the park alley. Who knows how it happened, but everybody in Brussels, who went to visit the first post WW2 World Expo 58, wanted to see the Czechoslovakian Pavilion. From the dark world of a cruel regime, a very bright project emerged. You could read about it everywhere, and just a few days before the end of the exhibition, it was clear that it will win the main prize. Whoever managed to get inside didn’t know what to see first – some people ran to get seats in the auditorium to see the unprecedented Polyecran of Laterna Magika, others hurried to the renowned Prague restaurant and some people went to admire art pieces made behind the Iron Curtain - and most of the time they were shocked by their originality and progressivity. One of the pieces, maybe the most original of them all and certainly unprecedented, was a set of “Glass stones” embedded in a concrete wall. These intoxicatingly colourful stones were full of light, and fascinating animal reliefs were shining bright as if they were created by a prehistoric hunter. Every world glassmaker who saw these stones was very excited. What is that? What technique is that? Who made this? It was Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. Their first foreign project. Well, but who are they? And why are they an artist couple?

Jaroslava Brychtová was born in 1924 in Železný Brod. Her mother Anna had an atelier at home, for hand-woven fabrics. Her father Jaroslav was a renowned Czech glassmaker, academic sculptor and teacher at State Technical Glass-Trade School. It was founded in Železný Brod in 1920 as a counterweight to North Bohemian German schools, and it became the first-ever purely Czech glass school. You might think – oh, so it is clear that Jaroslava will be a skilful glassmaker. Yet, it wasn’t exactly the case. Jaroslava defied her family tradition. Although, she admired her father´s work, especially his renowned figures from drawn and blown glass that won him a gold medal, she personally wasn’t drawn to glass. She decided to go to grammar school instead. The environment eventually decided. After graduation, Jaroslava applied to the Academy of Arts Architecture and Design in Prague and was accepted. Nevertheless, she didn’t start school, because it was the year 1944 and occupation forces closed the school down. And so Jaroslava found herself in a German factory in Železný Brod as a workwoman. She was able to continue with her studies after the War when she entered UMPRUM, the Atelier for Applied Sculpting and Engraving in Stone and Glass.

She was observing her father´s experiments with the technology of melting glass in a mould. It was an ancient technique that wasn’t used much then. It was only used for creating small reliefs and some kinds of brooches. Jaroslava was fascinated by that because it was much closer to her favourite discipline - sculpting. She joined her father, and they started exploring boundaries of rediscovered technology. Sculpting seems to be her future. In the end, she changes direction and goes to the Atelier of Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Let´s leave the fate of Jaroslava Brychtová aside for a minute, and let´s search for the beginning of her creative partner.

Stanislav Libenský was born three years earlier than Jaroslava. He was born in Sezemice near Mnichovo Hradiště, not far away from the Crystal Valley. It was close to the Lusatian Mountains and Turnov as well. His father was a blacksmith and farrier, so it seemed that poverty would force Stanislav to do something very practical that would bring food to the table. However, Stanislav loved pictures. His father Emil had to have some artistic talent because he often drew pictures of fairy tales for his son. And so, Stanislav fell in love. He wanted to become a painter. He longed for it. His teachers discovered his talent, worthy of developing, in the fourth grade. Stanislav was producing oil painting landscapes, here and there, he earned some money by selling them to local peasants. His father knew that to be a painter is quite an insecure living. He, however, felt his son´s passion for this vocation and sent him to the Secondary Vocational School of Glassmaking in Nový Bor. Nevertheless, young Stanislav soon transferred elsewhere – the Munich Agreement came and so with it the occupation of Sudetenland. And so, seventeen-year-old Stanislav found himself at a different school in Železný Brod in 1938. Železný Brod is not a big town. However, it was highly unlikely that he would meet a fourteen-year-old student of Elementary School - Jaroslava Brychtová. He was, however, meeting her father every day as he was teaching at the school. The next step for the young glassmaker was to go to UMPRUM in Prague. He didn´t meet Jaroslava here either – Stanislav successfully graduated in the same year that Jaroslava was accepted.

After the War, Stanislav Libenský returned to Nový Bor, where he became a part of a group of young and ambitious glassmakers, who were trying to make Northern Bohemian glassmaking truly Bohemian again. Stanislav works and teaches in Nový Bor, and in 1946, he gets married here as well. Yet his journey leads to Prague, to UMORUM, to the Atelier of Applied Painting and Glassmaking. Stanislav is logically considering returning to Nový Bor to continue with what he started after the War. Nevertheless, socialism needs, according to its leaders, heavy industry more than glass jewellery. And so, many factories from light industry are closed down, including glass schools in Nový Bor and Kamenický Šenov. So, Stanislav finds himself again in Železný Brod, at glass school - as a director. Who was his predecessor? Jaroslav Brychta. At that time, Jaroslav continues with his experiments with melting glass with the help of his daughter. But we know this story, and it goes full circle, the situation is ready for the crucial meeting. To add all the information, we must mention that Jaroslava was also married. She was studying AVU and had two sons. Just for the sake of interest, she got a glass furnace as a wedding gift from her father.

Železný Brod at the beginning of the fifties. Two major glassmakers work in one place. Jaroslava experiments further with melting into a mould. She tries bigger sizes as well. Despite being only twenty-six years old, she founds the Experimental Centre for the Application of Glass in Architecture, implements and installs the first projects. Meanwhile, Stanislav designs the motives and shapes of utility glass. He gets more and more interested in monumental painting. She is a sculptor in her heart - he is a painter.

The mid-fifties are coming. Jaroslava goes along the school corridor. Soft light falls inside. The atelier doors are open. Jaroslava passes a table covered with papers, sketches, drawings and statements. She suddenly stops. One of the drawings catches her attention. She steps back and takes the drawing of a woman’s head decorating a bowl. Bowl – head. She keeps the drawing. She cannot stop thinking about it. She knows that Stanislav drew it – the director. She goes to see him. “Mr Libenský,” she says, “could I try to turn this into a model?” Stanislav stretches out a cigarette, looks gently at his beautiful colleague and says: “Why not?” that is how it all started. It is interesting what such a significant moment of life looks like – mostly banal and mundane. No one could know that an amazing cooperation was born, which would last for nearly fifty years and would conquer the world. They both had no idea. The bowl – head turned out great, and it was breath-taking, yet neither of them thought it was important. What they knew right away was that they could enrich each other´s work by working together. And it worked! Soon after the bowl was created, they produced the head. And this was a true discovery. It had outer and inner relief. Besides, the light brought it to the next level. This wouldn't work with any other material - light as new expressive material. The light transforms colours, shifts the shades and reveals what´s inside.

And so, Brychtová and Libenský work together. They accept any challenge, enter competitions, so they don’t have to deal with banalities and they can explore. One of the challenges is the piece for the World Expo 58 in Brussels. The zoomorphic stones we mentioned at the beginning. The reaction is overwhelming, and rewards are coming as well - the Expo Grand Prize. Both Stanislav and Jaroslava are present at the installation of the piece. They explore the city and the exposition, and they know that what was only cooperation is much more now. Stanislav is married and Jaroslava as well, with three children. However, the feelings that were born unnoticeably, fully break out in Brussels. Suddenly, all is clear and simple – they will remain together in all sense of the word. In April 1963, their wedding took place. “I married the most beautiful girl in Železný Brod,” remembered Stanislav in later days. “I made the right decision, and I have never regretted it.” And what about Jaroslava? “I have also never had any regrets. The only thing is that when Stanislav got the position of the Professor of the Atelier of Glass at UMPRUM in Prague, he promised to come home often, during the week as well. He taught at that school for twenty-four years and he never once came home during the week!” So, it was a weekend marriage. Yet, it didn’t kill the marriage and even benefited their work. During the week, new ideas were born and they connected them over the weekend so that new art pieces could emerge. Some of them very unique.

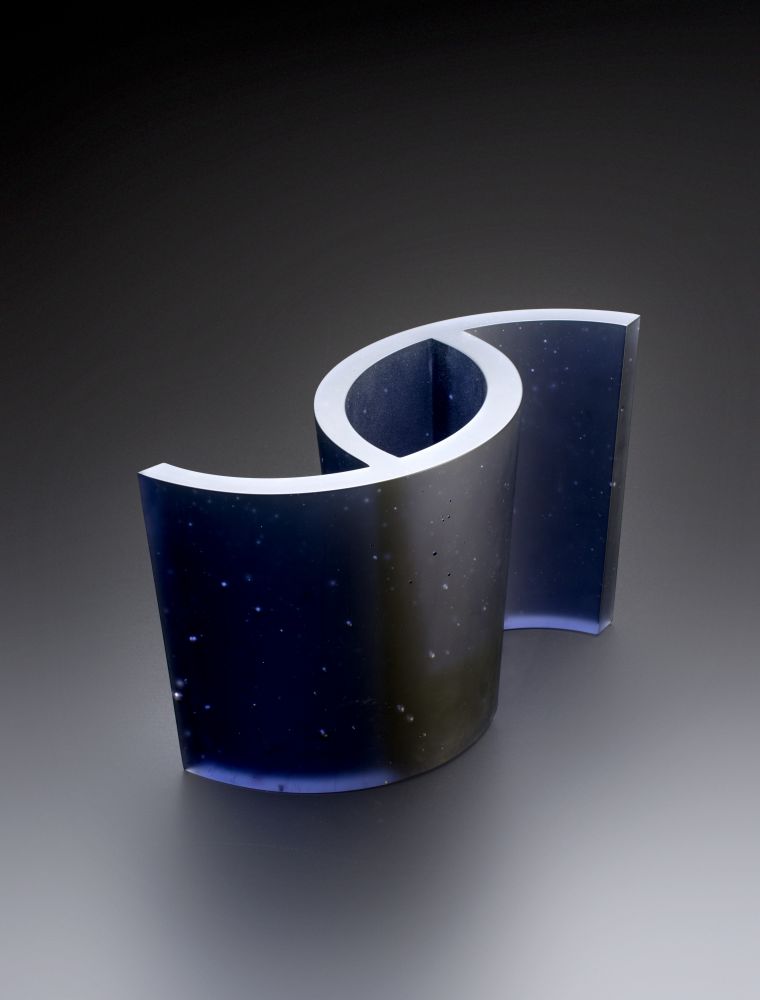

What was so unique about the work of Brychtová-Libenský? They were the first in the world to prove that glass art is at the same level as painting or stone sculpting. They brought the rediscovered technology of melting into a mould to a new level of new opportunities. They were also the first to use this technique to make huge objects. Their work produced pieces that moved architecture to a place where it has never been before. They started to install these art pieces as a part of architecture. They managed to enhance the solid shape of a building by adding the movement, which also adds light running through the art piece. They discovered the inner space of a sculpture, which was something new. They combined inner and outer reliefs. They never stopped exploring. They became probably the most famous and admired Czech glass artists, and their pieces are part of many art collections all over the world – in Perth, New York, Coburg, Los Angeles, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Joko Hama and others.

Very unique is also their work as a couple. Stanislav came up with the plastic elaborate drawing and Jaroslava did the modelling, and supervising the technology. She also invented the names of the pieces. What is fascinating is that they were creating everything in real size. For example, when they were designing windows for St. Vitus Cathedral, they had to expand their atelier to be able to fit in seven-metre high drawings. Models were also made in full size, cast from plaster. It was then transformed, using glue, to a mobile model, and then it was turned into a fireclay mould. Then they had to pour the glass into the mould and cool it down.

The cooling is the true alchemy. Some objects had to be cooled longer, some for a shorter period. And during the whole process, despite many years of experience, you still felt a great amount of fear that it might break. After Brussels, there came Expo 67 in Montreal and together came “Montreal Triptych”, three breath-taking sculptures that literary changed the world view of the glass art. Following Expo Osaka 70 and the famous “River of Life”. The glass installation was “floating” through the whole exposition, with imprints of girl´s’ feet and two girl´s’ bodies. Originally, there were supposed to be imprints of military shoes as well, which would add rather chilling content connected to events in distant Czechoslovakia. Usually, the Kerberos party did not consider abstract glass art as ideologically dangerous (they often thought there is no ideology), but this time, they felt the anti-occupation theme. They threatened to tear down the whole piece, and so the military shoes had to be ground into waves. The fame of this artistic couple rose significantly. Unlike most of the residents of Czechoslovakia, they travelled around the world, but very occasionally with each other, because the communists didn’t want to take such a risk. Another example was that only Stanislav was allowed to visit the Olympics in Rome. Jaroslava later travelled there with Čedok. How did they find each other there? Stanislav ground an agreed symbol onto little stones, and then hid them at different places around Rome. The symbol was a motif of one of their "heads" – " a kiss". It is this human level of their relationship and cooperation that allowed them to work together for fifty years. If it wasn’t for Stanislav´s death in 2002, their creativity would still go on. Mrs Jaroslava Brychtová, today ninety-five years old, continues to carry the idea of thei artistic couple.

Finally, let´s look at art pieces from Libenský-Brychtová. On the riverbank of the Jizera river in Železný Brod, inside a red house carrying their names, you can find a very unique exposition of their work. It will take your breath away. All artists, glassmakers, as well as ordinary people, are stunned by it. The glass “coat” of the new building of the National Theatre still shines today in the afternoon light. In Horšovský Týn, you can see the light going through the beautiful cast windows. In St. Wenceslaus Chapel in St. Vitus Cathedral, the sun lights up interesting glass windows, as if they were gates to another world. In the Oldtown Hall, there is the Crystal Wall that expresses a whole new dimension of space. Meltedglass sculpturinge, discovered by these two people from Northern Bohemia, lives on and on.

See & Experience

See & Experience